I have been unfaithful about 20 times in each marriage. That’s three times a year. But if it was only three, it was a bad year

Evening Standard | 2 Jun 1992

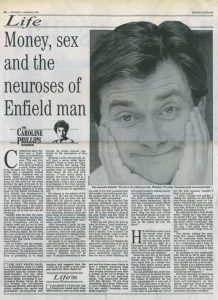

I’ve been unfaithful numerous times. I honestly can’t remember how many. Maybe 20 times in each marriage. About three a year for each marriage,’ laughs the man with the husky voice and drink-veined nose laughs. ‘But if there were only three, that was a bad year!’

The man talking to me was first married at 19 to early love Nora Ann Simmonds, by whom he had a son, then for 11 years to actress Tarn Bassett, who bore him a daughter and, most famously, for 10 years to Maggie Smith, with whom he had two sons. For the last 18 years he has lived with actress Patricia Quinn.

View transcriptI’ve been unfaithful numerous times. I honestly can’t remember how many. Maybe 20 times in each marriage. About three a year for each marriage,’ laughs the man with the husky voice and drink-veined nose laughs. ‘But if there were only three, that was a bad year!’

The man talking to me was first married at 19 to early love Nora Ann Simmonds, by whom he had a son, then for 11 years to actress Tarn Bassett, who bore him a daughter and, most famously, for 10 years to Maggie Smith, with whom he had two sons. For the last 18 years he has lived with actress Patricia Quinn.

He is Robert Stephens, the actor who was once talked of reverentially as Olivier’s heir, an electrifying, charismatic star who in one season in 1970 played four major roles at the National Theatre. His marriage to Maggie Smith became the stuff of legends. They became the first couple of British theatre. Then something happened.

Towards the end of the Seventies his career collapsed and he disappeared in a mist of obscurity, alcoholism and promiscuity.

Today Robert Stephens has made a triumphant return playing the greatest Falstaff in living memory in Henry IV Part I at the Barbican. His is a story – and it is writ large in his face – of self-destruction and rehabilitation, of despair and resurrection. We talk about his marriage to the said Miss Smith.

‘A long time ago,’ he says, ‘I was forced by a dentist friend to tell Maggie about my adulteries. He said, ‘If you don’t, I will’, so I had to tell her. Unfortunately, I’d had a slight romance with his receptionist who was also his mistress!’

Stephens often plays for laughs, but there is a sad figure behind the mask. ‘I think telling about an adultery is the worst thing you can ever do to a woman.’ Samuel Beckett’s line – ‘adulterers never admit’ – rings in his ears.

‘He might as well have given me a dagger to stick in Maggie’s back. I knew it would destroy our marriage. She was Scottish, puritanical, and doesn’t think of herself as being a beautiful or alluring woman.’ He lights a cigarette. ‘I never did any of these things with malice aforethought or capriciously. I prefer the company of women and have a great sympathy for them. In this business, you’re thrown together with people, sometimes when you’re away from home, and it’s very easy to become attracted.

‘You think you’re falling in love all the time, not just being a Don Juan who has to jump into bed with everyone he meets or he feels he’s not quite a man. But there’s always a reason why. Possibly you’re not happy in your own situation. There’s something lacking which you search for somewhere else.’ With Smith (‘definitely’ his most important past relationship), he blames his adultery on the fact that her career had started to take her over. Their separation, followed by divorce in 1975, was the beginning of his decline, both personally and professionally.

And was he faithful to Lady Antonia Fraser, in whom he then sought solace for a year? ‘Yes . . . mostly.’

Wearing gym shoes, an open-necked shirt and sports jacket, the 40-a-day filterless Camel smoker with hands that shake slightly has limped into the private room at the Royal Garden Hotel. Once described as debonair, flirtatious and irresistible to women, time and alcohol have now coarsened the textures of his face. ‘I always thought I was a rather plain-looking person.’

He dyes his hair so he doesn’t look ‘like Old Man Mo’ and has £8,750 worth of capped teeth, because he grinds his teeth in his sleep. He is limping because, following an operation on a fractured hip, one leg is now half an inch shorter than the other; he’s having built-up boots made. ‘You’re a cripple for the rest of your life.’

So what of his self-destructive streak? His sexually nihilistic tendency also manifested itself in his drinking habits. ‘I was drinking heavily about nine years ago so I went to a couple of meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous, but I found them boring,’ he says, defensively.

‘At one stage, I was getting through half a large bottle of whisky and a couple of bottles of wine a day. I didn’t use to smash things up or anything, but it makes you take wrong decisions and say things you wouldn’t want to say.’

He says he last had a drink two months ago, but that he hasn’t drunk heavily for nine years.

‘I had to give up because it was making me ill. I got diabetes and you tend, if you drink a lot, not to eat properly, which is very harmful for your system because you have all the sugar in the alcohol.’ He has to inject himself daily with insulin.

In addition, he almost died earlier this year. Exhausted after his Stratford season, he fell ill while on holiday in Palm Springs. He was found to be anaemic, given a blood transfusion, proved allergic to something in the blood and was given a 20 per cent chance of survival.

‘It’s an awfully expensive place to nearly die,’ he laughs. ‘My bill for one week was $59,000 and $750 for five minutes in an ambulance. But it did have policemen with pistols and everything, including a cocktail cabinet in it.

‘After they gave me the wrong blood, I woke up and couldn’t breathe. I thought I was dying. It was dreadful.’ Then he was given a drug which totally paralysed him. ‘I could hear voices talking about me, but I couldn’t say anything. It was like being tortured by the Gestapo.’

It could be that experiences like these have given depth to his acting, but he will have none of that. ‘I don’t understand why people always write that I understand failure,’ he says. ‘I feel proud of what I’ve achieved in my life. You don’t want to do rubbish, but you can’t sit and wait for 10 years for a big part to come up. The problem is that writers don’t write any more.’

Born in Bristol in 1931, he was the eldest child (he has a brother and sister) of a costing surveyor. ‘Home life was pretty bleak,’ he stumbles. His father was away for most of the war, building camps for prisoners. ‘I became the surrogate father or husband.’ His mother was away working a lot too. ‘So I had to look after my sister. It was curious having to look after a little baby when you were only eight yourself.’

On Stephens’s birth certificate, it says: ‘Father’s profession: common labourer’. He sounds slightly contemptuous and sad. ‘Well, that’s about the lowest you can go. It’s like digging up the street. But my father, being a clever man, did climb the ladder.’

Currently earning £600 a week and enjoying a ‘reasonable life’, Stephens hated his working-class childhood. ‘We were very poor, so one didn’t have an education.’ He went to Shire Hampton Boys’ School and left at the age of 14. He was often evacuated, sometimes with his mother. ‘So there was nothing constant in life.’

He says he wasn’t close to his parents, and that it wasn’t a big deal when they both died within the last eight years. ‘I left home when I was 15. If you do that and don’t go back except maybe for Christmas, then you’re not reliant on your family for anything. You have to get on with it by yourself. You have to create new families as you go from one repertory company to another.’

He hasn’t kept up with his siblings either. He talks about his brother as if he were dead, although he says there hasn’t been a falling out. ‘He was a silk-screen painter. I last saw him about 10 years ago. My sister’s married. She came last year to see me in Stratford.’

He keeps in contact with three of the four children from his marriages. He once got a note at the stage door when he was in The Murderer at Stratford. It read: ‘I am 21 and your son, but as we’ve not met since I was one, I’ll entirely understand if you don’t want to see me again.’ It was Michael, his son by Nora Ann. They saw one another for a few lunches. ‘Now we’ve lost contact. He’s in Canada, but I don’t know where.’ Fortunately, he says he’s happy now with Patricia Quinn, who is 13 years his junior. ‘Probably because we’re not married. I’ve asked her lots of times, but maybe she thinks marriage is the thing that destroys my relationships.’

She’s also more alluring because he hasn’t ‘got’ her. ‘I mean she might bugger off with someone else.’

He loves talking about himself. Stephens moves his hands a lot to speak, and verbally and with his body language he is mostly friendly, giving and effusive. Yet he has eyes that are mistrustful, sad and frightened. ‘Yes,’ he says, unconsciously covering them with his hands, ‘it was driven into me when I was little to be timorous.’ Being larger than life, acting, and being a charming and amusing raconteur is, ‘perhaps’, a cover for shyness.

And what of the character he plays? His Falstaff is not a drunken, stumbling oaf. He has a comic ability and a willingness to look at the darker side of life, never forgetting the hurt of rejection. Stephens says he is a tragic figure.

‘He’s not ha-ha-ha, hoo-hoo-hoo. He is a very tough, keen, highly intelligent man. Certainly, he’s a great survivor, and no believer in king and country or being a hero. He’s interested in himself and staying alive, not in honour. There’s that great speech where he says: ‘Honour is nothing . . . can you wear it, see it, buy a packet of cigarettes with it?’ Does he identify with the character? ‘Totally. You’re just talking about yourself.’