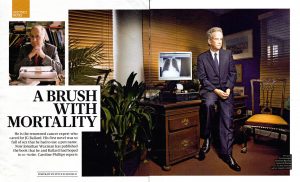

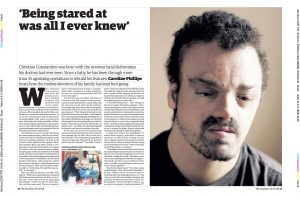

Christian Constantine was born with the severest facial deformities his doctors had ever seen. Since a baby, he has been through more than 35 agonising operations to rebuild his features. Caroline Phillips hears how the tireless devotion of his family has kept him going.

When Christian Constantine was born, the doctors at London’s Portland hospital had never seen such severe cranio-facial deformities. They didn’t, and still don’t, have a name for his condition, but he is believed to be one of four people in the world with a combination of so many rare and serious defects. At 23, he has endured more than 35 operations, including highly risky major reconstructive ones. He has also faced the possibility of blindness, had his kidneys operated on, gone deaf in one ear and suffered life-threatening illnesses such as meningitis and hydrocephalus (fluid on the brain that causes compression).

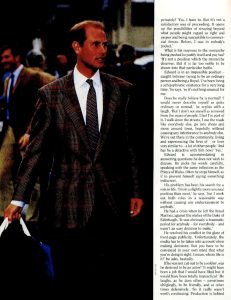

Yet Christian’s is a story of hope, determination and extreme bravery, which he has chronicled in a memoir for which literary agents Curtis Brown are seeking a publisher. We meet in the central London apartment belonging to Christian’s mother, Mina, and father, Adam, a company director; who are both Greek but were raised in London. With his scarred forehead, slightly drooping right eyelid and somewhat distended cheek, Christian is now taken by most people for an accident victim rather than someone born with a rare combination of disabilities. He talks from the back of his throat, with a nasal tone: speech that, owing to therapy, is vastly improved since he was at nursery, when only his family understood him. (“At the time, I thought that was normal,” he says later.)

Mina, 52, offers me biscuits, chocolate, fruit and tea. “I didn’t know anything was wrong until Christian was born and I saw my doctor’s eyes,” she says. “Then they put me to sleep again immediately. I didn’t see him for three days. Not until the nurses said, ‘First we’re going to show a Polaroid picture of baby to mummy.’ That’s when I insisted on actually seeing him. He was very wrong-looking indeed. But I felt love at first sight.”

The doctors were mystified. The bones of Christian’s face had stopped forming prematurely, he had hypertiliorism, which meant that his eyes were too far apart and his eyebrows abnormally high, and a severe cleft lip and palate, leaving the roof of his mouth open and the top gum exposed. (“That thing protruding from my lip is the roof of my mouth, I think,” says Christian later, showing me photographs, including one of his mother holding him adoringly, and another of him aged three and wearing a bow tie with his father.) “They didn’t even know whether he was going to live,” says Mina, who had him baptised in intensive care when he was three days old.

At the time, the doctors were particularly concerned that the frontal lobe of his brain had been damaged by the cleft, which went up to his forehead. “They mentioned putting him in a home and also said, ‘If he gets ill, we won’t try hard to save him, all right?'” says Mina. “I said, ‘I agree.’ That’s the only time I ever felt that, when I thought he might be brain-damaged and not have a quality of life. Happily, he was fine. He had his first operation at six weeks, to repair his cleft lip. But nobody had any idea that we’d still be operating nearly 24 years later.”

In the intervening years – from Chicago to Houston, London, Paris and Los Angeles – Christian has undergone a series of radical procedures (including moving his eyes and building a nose) as well as operations to create eyelids, to put bone grafts in his mouth to support teeth implants and to prevent urinary reflux (when urine flows back to the kidneys). In 1985, he had surgery at Great Ormond Street to correct his compressed head bones – his brain was growing faster than his skull would allow. Surgeons opened his head from ear-to-ear to release the bones. Shortly afterwards Christian got meningitis and hydrocephalus.

In 1993, Paul Tessier, the “grandfather” of cranio-facial surgery, performed a massive procedure on him in Paris to bring his eyes closer together and lower his eyebrows. Before the operation, Adam overheard Tessier saying to his anaesthetist in French, “We’re entering a patch of fog without a compass.”

“They had to remove the entire bone from my face and reshape it and my brain was ‘shrunk’ to allow more room for the surgeons to work,” says Christian, straightforwardly. “Blindness was a risk, as was exposing my brain after meningitis.” Afterwards, he threw up a lot of blood. “Obviously, I couldn’t see anything because my eyes were stitched together.”

Was this his lowest point? “I’ve often woken up and thought, ‘This is physically unbearable,'” he says. “When I was 19, they had to correct a forehead defect by applying pressure to it. The only way to do this was to staple a bandage onto my head. To remove it, they had to yank it out. Excruciating.” Once he had tissue expanders (which are similar to balloons) placed inside his head and then inflated with water to stretch the tight, scarred skin. “They put water through a needle into a tube inside my head and then the expander got bigger and bigger under the skin. It was agony.” Another time, when the upper lip was being improved, his lips were sewn together for two weeks.

Despite all this, he recalls junior school as a “happy” time. “He was so cute and outgoing when he was little,” remembers Christian’s 21-year-old sister, Isabella. Aged 12, Christian played the lead part in the school play, and loved it. “I was dressed as a woman in a bright red wig and skirt,” he says. And what of unwanted attention? When he was nine, he tells me, the children at a party ran up laughing, “Look at his face, he’s an alien.” Another time a boy taunted, “That must be a mask you’re wearing.” “Once,” says Christian, “somebody was staring so much that he tripped and fell over in the street.”

“His being stared at was the worst thing for me, more upsetting even than sitting in hospital waiting rooms,” says Mina. “It doesn’t matter how educated people are, they can be awful.” In the street, his parents and sister would stand in front of Christian to block him from view. “I’d talk loudly to him,” says Mina, “so people would know that just because he didn’t look right didn’t mean that he couldn’t understand what they were saying about him.” At first, Christian wasn’t aware of the attention. “When I was young, it didn’t affect me that much because being stared at was all I knew,” he says. “But once I got into my teens and went to secondary school, it was terrible.”

Schoolwork was hard because he was off sick so much, sometimes for more than a term at a time. (He scraped through his GCSEs, but failed his A-levels.) And once his adolescent peers started partying and chasing girls, Christian withdrew into himself. His problems were exacerbated by his stunted growth. Aged 13, he wasn’t even 5ft (he’s now 5ft 7in). “By 15,” he says quietly, “I’d lost my confidence. I hated my looks, felt deserted by my friends and avoided social activities.”

He developed feelings for a fellow student. Did he tell her? “Of course not,” he smiles.

“I used to tell myself, ‘Who’d go out with someone as bad-looking as me?’ Then one day some boys started jeering, ‘Who do you think you are? The way you look, you don’t have a hope of

getting a girlfriend, ever.'” He looks down momentarily. “If I saw them today, I’d break their legs.” Did his parents consider therapy for him? “I didn’t tell them what was going on.” Mina nods. “I only heard about a lot of this recently. But anyway there weren’t

support groups that I knew of,” she says, “and he didn’t ever want to be grouped with people just because of having deformities.”

When he was 16, his closest friend since childhood, George, died. “That hit him really badly,” says Mina. “Not least because it shook his faith in medicine. Until then he’d always thought doctors could fix anything.” He started skipping school to drink beer at 11am. “At night, I’d wait until my parents were asleep, then drink a bottle of wine,” Christian says. Depression took hold and he’d sit listlessly in the waiting room on the floor where George’s bedroom had been in the Royal Free Hospital. “I’d go there after midnight and sit there for hours just looking straight ahead.”

“I knew he was devastated about George, all his friends were, but I didn’t realise anything else was going on,” says Mina sadly. “He hid it so well from us.” At his GP’s suggestion, Christian had counselling in 2001. “It wasn’t much help but I never wanted psychiatric care,” he says. “I’m not very open. I don’t talk about my problems.”

His difficulties came to a head when he was studying shipping at Southampton University in 2004. “I’d thought everything would be different there,” says Christian, who took a year out in 2005 to have an operation to lower his eyebrows and hairline. “But after a few weeks, I’d hardly talked to anyone. I’d just go to lectures, then back to my room. I was drinking to escape my problems. I didn’t even dare go to the common room. But I told mum and everyone that I was loving it.”

One evening in October 2004, he walked back from a bar resolved to take his life. Back in his room, he grabbed 20 Panadol Extra. “I didn’t even know if it would be enough to kill me,” he says. “But it wasn’t really a suicide attempt. I didn’t even try.” It was seeing a photograph of his family that stopped him. “That brought me to my senses. Whatever I’d been through, they’d suffered too.” He was hysterical when he rang his Uncle Basil, who calmed him down. “It’s the first I’ve heard of a suicide,” says Mina, with surprising calm. “I think he’s shielded me from lots of things.”

Unsurprisingly, the impact of his disabilities on the family has been great. “I adore him now,” says Isabella. “But for obvious reasons he got most of the attention when we were children. I was very jealous.” Often when the family went to operations, Isabella had to stay with relations.

Adam and Mina’s stable 26-year marriage has inevitably suffered. After giving birth to Isabella in 1987, Mina terminated two further pregnancies for foetal abnormalities similar to Christian’s. In 1988, after her first termination, at 22 weeks, Adam walked out. “Only for a few weeks,” says Mina. “We both wanted another child and were coping with Christian, but another abnormal baby was too much to bear.” She pauses. “I also had a sort of breakdown after my second termination. Things got progressively worse and culminated, finally, in a nasty bout of pneumonia, for which I was hospitalised. I’m sure it was psychosomatic. I always felt that I didn’t have anywhere to go and cry.”

The high financial cost of Christian’s treatment is also clear. Their health insurers, PPP, underwrote most of the early procedures that were carried out in the UK, but the Constantines have had to pay for other operations, plus their worldwide travel and hotel expenses. “We had to. They just wouldn’t have been able to do things like the nasal reconstruction and lowering his eyebrows here,” explains Mina. “They made sacrifices,” adds Christian simply. “But they were always clear that they’d do whatever was best for me, whatever it took. And, frankly, plastic surgeons are light years ahead in the US.”

Christian’s immediate family has been ceaselessly supportive and protective of him. “I think I helped him psychologically with my positivity,” says Mina, who has dedicated her life to making things better for him. “I also taught him to be a bit arrogant, as a defence and protection.” Isabella says she still “babies” her brother and always keeps her eyes and ears open for him, “although he’s more than capable of doing anything himself”. Meanwhile Adam has worked tirelessly, researching the best doctors, paying for and attending operations. (“Adam is intensely private,” adds Mina, “but he’s had his dark moments. Once they stuck a massive skin graft on Christian’s face and it looked like a croissant under his nose. I think that’s when Adam wanted to pitch himself out of the 46th floor of our hotel.”)

Christian also has a close extended family (he has 20 first cousins). “He was treated as normal by them,” says Mina. Many would fly to lend support at operations. (The Constantines travelled 14 times to Chicago in two years, and spent two months in LA at a stretch, for operations.) “Adam’s siblings, their partners, my in-laws, my mum and granny, about 20 of us, went to Paris for Christian’s operation in 1993,” says Mina. “I’ve only ever attended minor operations alone.”

The doctors still have no idea why Christian’s problems occurred. Last year the Constantines saw geneticist Prof Raoul Hennekam at Great Ormond Street. “He’s still researching,” explains Christian. “He says there are only four similar cases in the world.” If the defects appeared in Christian’s children, what would he do? “I’d want to terminate,” he says. “I don’t want to sound arrogant, but I can’t imagine anyone else surviving what I’ve been through. I couldn’t let my child go through what I’ve suffered.”

There’s a sense, however, that Christian is coming to accept his lot. Step by step, he’s confronting his problems. He feels he has his drinking more under control. “Sometimes I don’t drink for a week,” he says. “If I drink, I can’t stop. So I have to be careful. I’ve thought of trying AA. I think I’m doing it now because I’m addicted to alcohol rather than to escape problems.”

“He seems to have come to terms with things more,” confirms Mina. His appearance and self-esteem have improved radically. Now, in the rare event that someone stares, he stares right back. He has also made good friends at university. “Not just relations and Greeks!” he laughs. He’s finishing university this year. “For a change, it looks as if I’ll pass my exams.” After graduation, he’s thinking of living in New York. And he hopes one day to marry and have children.

Importantly, his major surgery is now over. “I may do a few more cosmetic things and have an operation to improve my speech.” He pauses. “Some people think I’m obsessed with looking perfect. But if anyone told me I couldn’t ever have another operation, I wouldn’t be terribly upset.” Really? “Honestly. It’s taken me a long time. But now I really do feel that it’s what’s on the inside that counts.” Which is someone funny, energetic and resourceful. And, of course, incredibly brave.*

*Some names have been changed.